With mild winters, plenty of open space, and endless opportunities for outdoor recreation, it's easy to see why Colorado is one of the fastest-growing states in the US.

"We were tired of having to spend nine winter months indoors without the sun," Ashley O'Connor, who moved to Colorado from Chicago in 2015, told Insider. "We like to joke that we traded skyscrapers for mountains."

O'Connor and her husband are hardly alone. According to census data, Colorado was one of the fastest-growing states from 2010 to 2020, increasing its population by nearly 15%. Colorado real estate has also been booming for years and experienced an even greater boost during the pandemic as urbanites ditched cities for less crowded spaces.

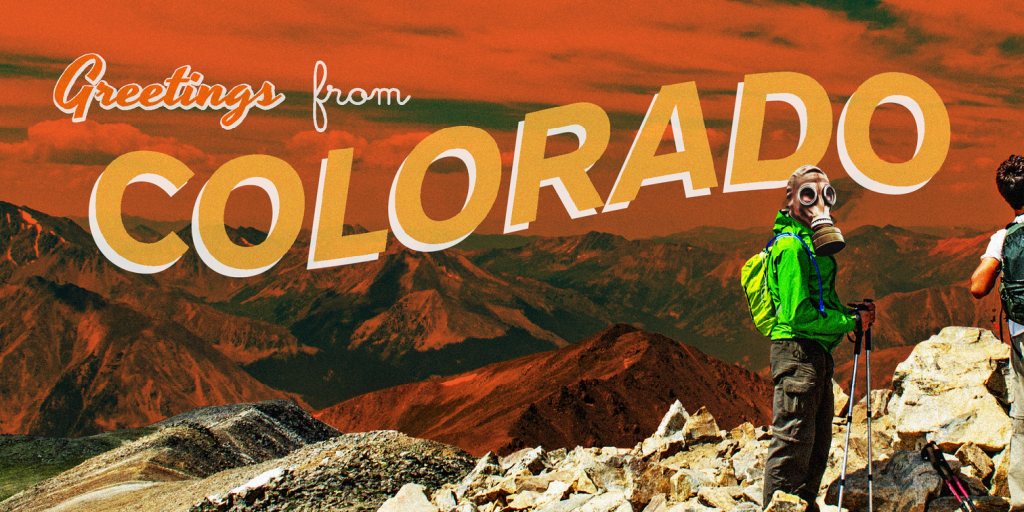

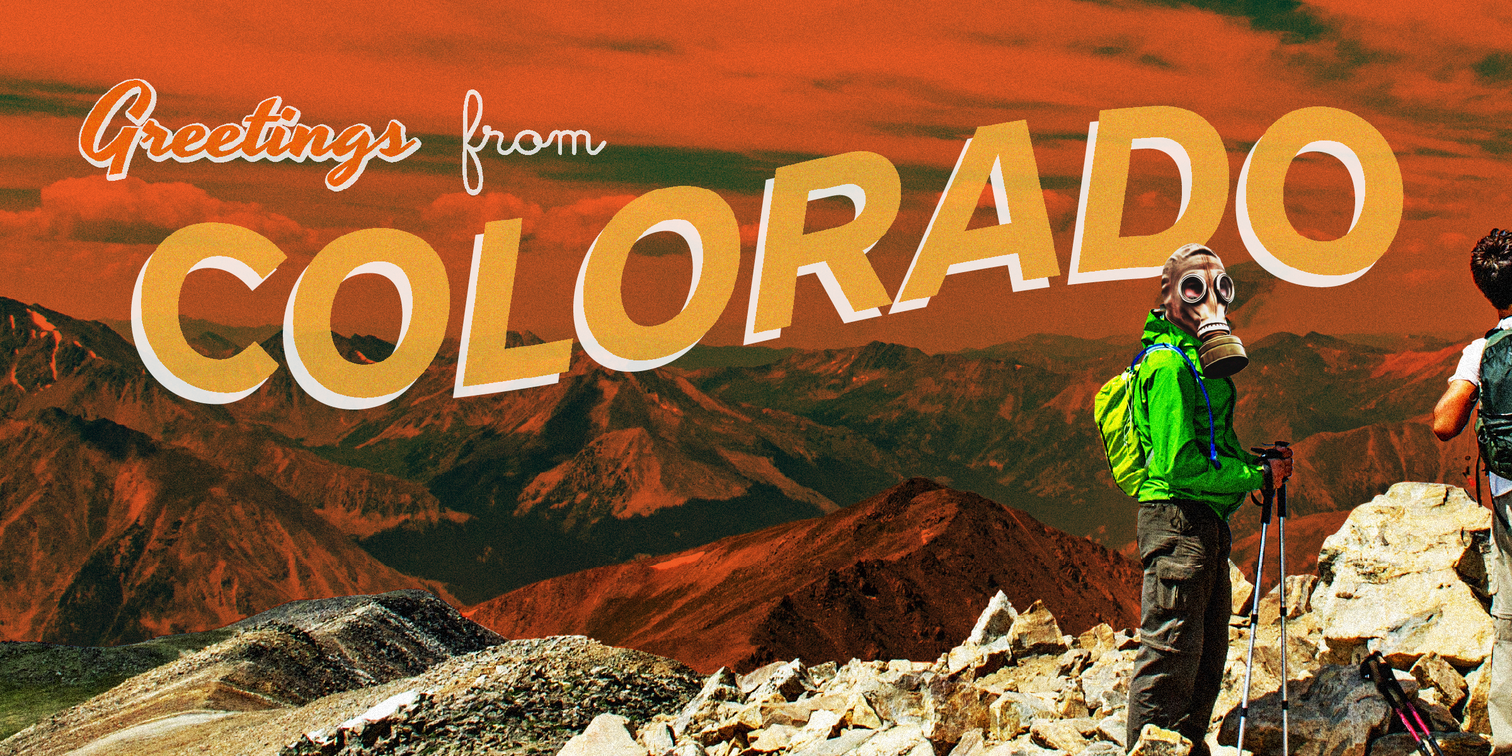

But one of the state's biggest draws – abundant access to the outdoors – is under threat.

The air in Colorado is getting dirtier, resulting in more days where haze obscures the mountains and when public health officials say it's unsafe to be outside, let alone do something active.

"For the last three months, three out of four days were air quality alerts," Frank Flocke, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, told Insider in mid-September. "We just had a clear day for the first time for weeks, where you could actually see the mountains."

Hyoung Chang/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post/Getty Images

Ozone pollution and wildfire smoke are largely responsible for obscuring the view of the Rocky Mountains, an increasingly common sight in Colorado, according to Flocke.

This summer, Colorado public health officials issued an ozone alert every day from July 5 to August 14, marking a 41-day stretch of air quality warnings. The state issued 65 ozone action day alerts from June through August, more than any year since 2016, when the current ozone standard was set.

'Hazy, smoky mountain ranges have become a bit of a regular sight'

For longtime residents, the change in air quality, and the impact it's had on their outdoor life, is evident.

"Honestly, it's heartbreaking," Susanna Joy, who has lived in Colorado most of her life, told Insider. "Those of us that are from here have noticed a really big shift in our ability to enjoy life how we grew up."

Joy said she grew up outdoors and remains an avid hiker who loves camping and being outside as much as possible. She said air quality and wildfires weren't even on her radar growing up, a stark difference from recent years.

"I never thought about air quality when I was planning outdoor adventures and now it's something that we look at consistently," Joy said.

Now, she gets an email every morning from a local newspaper that tells her the air quality for that day, so she can decide if she even wants to think about doing something outside.

"There's been multiple times where we're planning a 40-mile bike ride and we just don't do it because the air quality is too bad or it's too hot," she said.

Checking in on air quality has become a daily part of many Coloradoans' lives. The air quality index, or AQI - a tool used by government agencies to convey to the public how safe the air is on any given day - has become as common a discussion point as which 14er, or mountain peak higher than 14,000 feet, is hardest to hike to.

Even for recent transplants, the change is palpable, according to O'Connor, who lives in the Rockies in Summit County, home to some of the state's most popular ski resorts, like Breckenridge and Keystone.

Being outside "isn't just about hobbies, it is a way of life," O'Connor said. She loves to ski, bike, take her sailboat out on the Dillon Reservoir, and hike the many trails located minutes from her home.

But the "hazy, smoky mountain ranges have become a bit of a regular sight since moving here," she said. "Not only has it affected the amount of time we are willing to spend outdoors, but how we spend it."

O'Connor said she and her husband even wake up sometimes with "red, burning, itchy eyes" and congestion due to the poor air quality.

David Zalubowski/Associated Press

The culprits: 'A product of our own doing'

Ozone is the primary pollutant taking a toll on Colorado's air, according to Flocke.

Colorado has some of the worst ozone pollution of anywhere in the US. In 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency reclassified the Denver area as a "serious" violator of federal air quality standards. The agency gave the state until July of this year to get the ozone pollution under control, but that deadline came and went.

Ozone is a naturally occurring and man-made gas found in Earth's atmosphere. High-altitude ozone, like that found in the ozone layer, protects the planet by absorbing UV rays from the sun. Ground-level ozone, on the other hand, is emitted by things like cars, chemical plants, and oil and gas refineries, and enters the air we breathe.

Flocke said ozone pollution is "mainly a product of our own doing," calling transportation of people and goods and the oil and gas industry the "elephants in the room" when it comes to cutting ozone emissions.

A 2019 study co-authored by Flocke found the fossil fuel and transportation sectors were the major contributors to ozone on Colorado's front range.

Thomas Peipert/Associated Press

The millions of recent Colorado transplants aren't helping the problem, as the increase in population and traffic only causes those emissions to rise.

Breathing ozone can lead to serious health effects, according to the EPA, including coughing, throat irritation, chest pain, and shortness of breath, as well as longer-lasting issues like declining lung function. There is also strong evidence linking higher ozone levels with asthma attacks, increased hospitalizations, and increased mortality.

Sensitive groups, including older people, children, and people with respiratory issues are especially at risk, but high ozone levels can trigger symptoms even for people who aren't at higher risk.

'The fires make everything worse'

Those impacts are only magnified by the other pollutant permeating Colorado's air: fine particulate matter from wildfires. Particulate matter, or PM pollution, refers to tiny particles found in the air that are so small they can be inhaled when breathing.

"The fires make everything worse because they add the particles to the ozone," Flocke said.

The particles emitted from wildfires can get deep into the lungs and even the bloodstream, according to the EPA. Studies have linked PM to premature deaths in people with heart or lung disease, heart attacks, decreased lung function, and respiratory problems.

Even in years when Colorado has a relatively mild wildfire season, like this year, the state still deals with dangerous levels of PM blown in from other parts of the West. This year, fires in California and Oregon brought hazy, smoky days all the way to Colorado.

Alex Edelman/Getty Images

"They made a lot of the days multiple pollutant warning days, where you had ozone exceed the standard and particulates exceed the standard at the same time," Flocke said. "For people that are sensitive to pollution, that really makes it hard to be outside and enjoy life."

Flocke said the issue is worsened by the fact that the meteorological conditions that prevent the local ozone from being flushed out by cold fronts are the same conditions that bring in the wildfire smoke from the coast.

'If we tackle the climate problem, we will slowly also tackle our air quality problem'

The impact of wildfires on Colorado's air quality is unlikely to let up so long as the climate continues to warm, according to Russ Schumacher, director of the Colorado Climate Center at Colorado State University.

"Many studies, going back 10 to 15 years, have projected that the amount of acreage burned of wildfires in the West was going to increase as the climate warms," he told Insider. "We're starting to see that now."

Schumacher said the wildfires aren't solely due to climate change, but that climate change and the related droughts and heatwaves have set the stage for these big fires.

Climate change and air quality are "intimately connected," according to Flocke: "Our lifestyle causes emissions of CO2, which exacerbate climate change, which exacerbate the fires, which exacerbate our air quality problems."

Helen H. Richardson/ The Denver Post/Getty Images

But, he said, both crises could be addressed in Colorado with many of the same actions. Enacting tighter regulations on oil and gas emissions, improving public transportation, and disincentivizing driving would all help cut greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants.

"If we tackle the climate problem, we will slowly also tackle our air quality problem," Flocke said, adding that the solutions are "clear" but that there needs to be political will to actually implement them.

He said the increase in awareness about air quality, partly driven by the wildfires and climate change, could result in a greater push for change. The many transplants moving to the state could have a positive impact on that as well.

"People move to Colorado because they have this idea that we have clean mountain air," he said. "Maybe they will be more susceptible to accept stricter regulations."

Joy echoed those sentiments, saying she's "hopeful that this isn't just how summer is now, because I enjoyed summer so much as a kid."

While she personally tries to minimize her impact on emissions, she said she's also trying to come to terms with the fact that "until we make some big changes that help us reduce the impact that we're having overall, it's not going to change. It's going to continue to amplify."

Have a news tip? Contact this reporter at [email protected].